Mohabbat Zindabad

Musician Ankur Tewari and Ashtanga Yoga Teacher and Poet Scott Johnson use their artistry to bring love where there’s hate, life where there’s death and healing where there’s hurting.

I met Scott Johnson’s voice before I met the rest of him. In June last year, I was invited to a debate about whether or not India’s International Day of Yoga is a relevant day to celebrate, and Scott (Founder, Stillpoint Yoga, London) was on the panel of people discussing the topic on Clubhouse. There were around six people participating in that debate and Scott’s voice was the softest and quietest, but the one that affected me most. He chose a few words to express himself but each word held depth and meaning. After the debate, I looked up Scott online and found his page on Instagram. Scott writes Haikus, little gems of wisdom that possess a lightness of being and make you feel like everything is going to be ok.

I got in touch with Scott, and over the past few months, we’ve exchanged poems, opinions and life experiences. I asked him for this interview for The Yoga Life because in addition to being a brilliant writer, he’s also an uncommon yet effective Ashtanga teacher. I say uncommon because his approach to teaching is flexible, approachable and puts the focus on the student while also respecting the practice. Ashtanga follows a systematic sequence and it requires tremendous talent and knowledge for a teacher to maintain the system and at the same time make it work on an individual level for each student that practises. Scott does this with finesse.

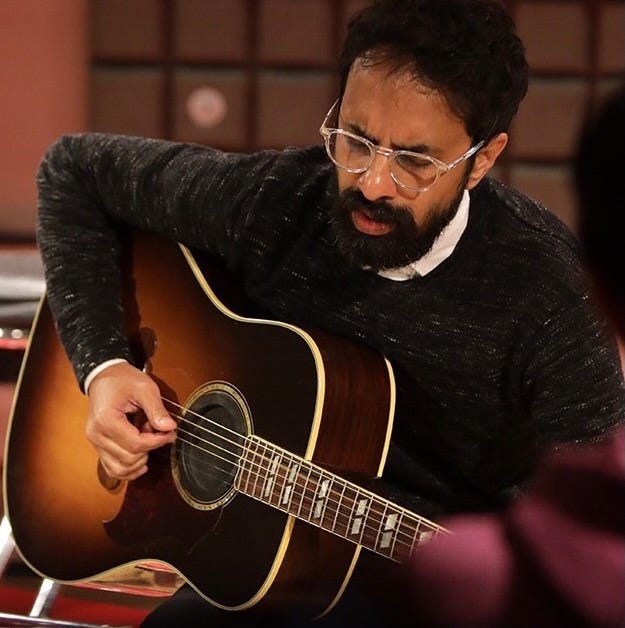

His artistry with words and the Ashtanga practice reminded me of another friend who uses music in much the same way. Bombay-based Ankur Tewari is an uncommon musician. I’ve known Ankur for almost 15 years and witnessed the making of his first album at a studio in Lower Parel, Bombay. This was in the early 2000s and the indie music scene in India was nascent but gaining currency because of shifting tastes and because by then, India’s MTV generation had paved the way for audiences to appreciate music that wasn’t restricted to songs from Bollywood. But even then, for a musician to write, produce and promote his own music was a daunting task but Ankur did all three and even played live. What’s more remarkable is that his signature style — with its minimal sound and restrained lyrics was original and new, and Ankur had the courage to trust his music and believed that it would find an audience.

Once Upon a Time…

Scott attended his first yoga class on Varkala beach in Kerala, India, while on vacation in India. “It was in 1998. I was 25 at the time and decided to take time off and travel. I even bought an open ticket and it was the first time I did something like that. We were on a beautiful beach in Kerala and my cousin suggested I attend this yoga class that was held at the place we were staying at every morning. I remember being very impressed by the teacher and liked how the practice made me feel. I attended the class during the time that we stayed there but when we left, it’s not like I continued practising but I did remember that this practice made me feel differently. We travelled for another 15 months and when we got back to the UK in 1999, I wanted to take up an activity that allows a relationship with my body. I remembered the feeling I got when I had practised yoga in Kerala, so I found a teacher and started practising. The thing with yoga is that there isn’t one single moment (at least for me) when the practice lands on you. It was a layered experience made up of various little moments. The teacher I was practising with in 1999 was also a Shiatsu teacher but she made us do yoga postures as well and I remember clearly it was in Trikonasana that I first felt my body soften and let go, and I was like, ‘Ah! So that’s how it’s supposed to feel.’ That was the first monumental shift I felt in me,” says Scott about his initial experience with yoga. “A year after that, I discovered Ashtanga and that was when I really noticed changes and those changes affected my life and I felt my awareness shifting. This was in 2002, when I was travelling in Australia. I had read about Ashtanga but I didn’t know what vinyasa meant or how the practice works but when I attended this class in Australia, I came out feeling like I found the thing I want to dedicate myself to. When I returned to the UK, I met Ashtanga teacher John Scott and that was the tipping point for me — John led me to where I find myself now and I knew even back then that I had found a teacher who would imprint something profound in me and I think that’s when practising yoga truly started for me.”

While Scott was beginning his spiritual journey in London, back in Bombay, Ankur had finished college and realised he needed to think about a career. “I’ve been writing songs and making music since I was in school. I never thought of music as a career and never made songs with that intention. I didn’t grow up thinking about a career. That could be because I grew up in a very nurturing, protective environment. It was only after college that it occurred to me that maybe it’s time to think of a career, so I figured I might as well do what I like doing and earn money doing what I love,” recalls Ankur. “It wasn’t easy to establish a career in music but it wasn’t hard either because I enjoyed it so much. I never thought of my work in terms of easy or hard. If I took time to think about it and focus on the hard, it could be seen as a difficult journey but I never took that approach. I have so much fun doing what I do and I face experiences as a new adventure. Each day brought so many challenges and it was like a game to me, so I played the game and I enjoyed the game. I was having fun. My journey also led me to meet several interesting people. I was learning new things about music, about song writing — my learning continues even now. I met so many musicians and most musicians are interesting people with interesting personalities. I won’t say the journey was easy but it wasn’t hard either because I was entertained throughout.”

An Application of Practice

I decided to interview Ankur and Scott for this piece because both create positive change through their work, and both have a talent to navigate through life’s challenges with grace and acceptance. Scott’s transition from practising yoga to teaching yoga wasn’t a planned move. Mysore is known for its Ashtanga authorisation and a majority of teachers travel across the world to receive an authorisation from the Mysore shala to teach Ashtanga. Scott’s case was different because while he does follow the lineage, his journey to teaching wasn’t deliberate or based on ambition, it happened because life chose that path for him. “I live in a small village on the outskirts of London and I had a young family, so I found a teacher locally. I was enjoying exploring the practice and I kept practising with John Scott whenever I could. I was in the Ashtanga honeymoon phase (laughs). But the teacher who was conducting the class decided to move to Spain and asked me if I wanted to teach that class and take over from him. I was only practising for two years so I wasn’t sure if I was ready to teach but I knew that if I didn’t take that class, the classes would probably end, so I decided to give it a go. That’s how I fell into teaching (laughs). Based on my learning with John and Lucy Scott, I knew the self-practise method was the way I wanted to conduct my classes, too. I continued to deepen my practice with John and still had a full-time job because I had a young family with three kids and a mortgage but I decided to teach anyway because the experience felt meaningful to me. The practice and then teaching it helped me to connect with myself. It was the first time in my life that I found something that spoke to me deeply. Learning from John helped me establish connections and relationships and understand myself and I wanted to share that feeling with other people. It was that quality of sharing that compelled me to pursue teaching. Yoga helped me to grow as a practitioner and as a teacher, and it allowed a sense of sensitivity that made me see myself in a new way. I didn’t have that before. Another reason why yoga worked so well for me is that I grew up in an alcoholic family so I had a very negative upbringing. In my early 20s, I was moving in and out of depression a lot and yoga was the thing that helped me understand how to be better. I felt that if I can feel this way, I have to share that with someone else and that’s what convinced me to start teaching,” says Scott.

In Bombay, Ankur was on the threshold of a music industry that has changed and evolved radically over the past 15 years. “The music industry for both live and recorded music is not what it was in the 80s and 90s when only a few music directors monopolised the industry. There are a lot more avenues for musicians and bands to showcase their talent. Technology has played a huge part and it’s not as difficult to record music as it was earlier. When it comes to live music, there are more venues, more festivals and if one is good at their work, it’s a viable career. The industry has done well because everything got digitised, the copyright laws have changed, and because of that musicians get more royalties and there’s a lot more money being invested into the industry and with that, more music is being created and people have become more open to listening to different kinds of music. It’s interesting because now there’s a lot more people producing music so there is also a lot more competition and that can make things hard. Like earlier, you may have been one in a 100 but now you’re one in a million (laughs). The scene for live music is very good at the moment. There are so many bands playing live and there are great venues in several cities — artists can tour the country and even internationally there is a market for it and people appreciate the music. In fact, there is a whole section of people who only listen to independent music and not mainstream music so the live scene is thriving. Of course, the past two years haven’t been great because of COVID. But other than COVID, live music has a big audience — in music festivals, college festivals and even in cities there are live venues almost every weekend. And it’s not just the young crowd, even older people are appreciating independent music and new sounds — and it’s a paying audience, people buy tickets to watch live shows,” explains Ankur.

“Even in films, there is more use of independent musicians and the way music is used in movies is changing — it flows with the narrative as opposed to being a random song inserted at random points in the story. In the near future, I wouldn't be surprised to see young, independent talent directing a film’s music score. I’ve worked on music for films but I wouldn’t say it was a transitional experience for me. I don’t change the style of my music just because it’s being made for a film. I feel musicians should create interesting music, so the audience will want to be a part of the experience regardless of the medium. Of course, I consider the script of a film when producing music for a film as the script is sacrosanct and the music has to flow with it and elevate the story and the feeling of the scene where music is being used. But I wouldn’t say that creating independent music or music for films is a different experience for me because I don’t classify music as Bollywood or independent — the difference is in how the music is promoted. There’s a lot more money that goes into producing and promoting the music for a film as opposed to independent music.” I can vouch for Ankur’s statement here because if you’re familiar with his music, you’ll find romanticism even in his rebellious tracks like the music he produced for Zoya Akhtar-directed Gully Boy (2019) or the soundtrack for Netflix’s Guilty (2020), he was also the music supervisor for the films Aao Wish Karein (2009), Raat Gayi Baat Gayi (2009) and director Shakun Batra’s soon-to-be-released Gehraiyaan. Ankur’s sound has evolved, too, but it’s still an Ankur Tewari sound and you’ll hear it within seconds of listening to his new music, “I like a minimalist approach in the story-telling of my music — an economy of musical notes and words works better for me rather than overpowering a track with too much noise.”

Finding Light in Life’s Dark

Talking to Ankur and Scott, it’s hard to believe that both have had to deal with all the difficult emotions that reality and life have a tendency to throw at us but what makes these men remarkable is how they managed to deal with even the most unpleasant reality that life has to offer. There is not a trace of jadedness in either and both find tremendous beauty in life’s ugly and create art from it. For Scott, this lesson came when he lost his business partner and friend Ozge Karabbiyik. He met Ozge at a workshop he was attending in New Zealand — the course was being conducted by John Scott, and Ozge and Scott were the only two people there from London. “We connected like brother and sister, and when I left after the first month, Oz wrote me a letter saying how she treasured our connection and friendship and she asked if we could teach together. I’ve always wanted to teach Mysore-style and I knew if we had to make this work, it would have to be in London. So when she got back to the UK, we found a venue in London to set up a Mysore-style programme. Stillpoint came from a vision to share Ashtanga the way we learned from our teachers,” recalls Scott. “We created a space that made people want to smile, to live, to feel joy and all of these important qualities that yoga inspires. But then Oz passed away in the beginning of 2012. She would visit Kovalam in India every year and spend five to six weeks there and on this particular trip, she had a tragic fall that took her life. She was only 34. I’d never lost someone so close to me and I lived the whole experience in slow motion. It was the 1st of January and I was at my computer trying to send out a newsletter to all our students about Oz’s accident. I had asked John Scott for help with this and while I was in the middle of writing this email, I received a message that Oz had died. I remember that visceral moment — I felt it in my body, and I said to John, we have to change the context of the email because Oz died. And that was the hardest email I have ever had to send to anyone. I had to inform these 500 students that Oz had passed. That our teacher, our friend and sister had passed away, and then pressing the ‘send’ button on that email was the hardest button I’ve ever had to press.”

When I started this interview with Scott, the Internet wasn’t cooperating so we switched from video to audio mode on Zoom and I couldn’t see Scott. But, I could hear the anguish in his voice and feel the honesty of his emotion — few men can be so vulnerable and strong simultaneously. “Our Stillpoint room was at Guy’s Campus, and it was a holiday the next day but I asked them to please open for us cause I knew I had to be in that space, and also our students needed that space. We kept a photo of Oz in the room and lit candles and just sat there in silence. All I could hear in my head was one sentence repeating itself, ‘What do I do? What do I do? What do I do?’ The impact of her passing was so profound and I had no idea how to begin to deal with it. I kept staring at her picture and the repetitive sentence of helplessness faded and instead I saw Oz in my head and she whispered to me, ‘you know what to do.’ It gave me all the strength I needed. I looked around at all our students and I knew what I had to do. I got up, gave each of them a hug and said, ‘Whatever she meant to you, don’t let that die because that is how she lives.’ We had to deal with loss but we had to remember what she means to us because that is how we keep her memory alive. We mourned for Oz for five days and on the last day, we invited her favourite kirtan teacher to chant at the shala and that was how we bid farewell to Oz. The energy was stunning and powerful and vibrant, just like Oz. The following week John Scott came to visit and I shared my sorrow with him. I was still trying to accept that I have to be there for my students and continue Stillpoint without Oz. He gave me the best advice anyone has ever given me. He said, ‘Every time a student comes to Stillpoint, you will open the door, give them a hug and say, how are you? They will let you know. Then you ask them if they are ready and if they say yes, then you say, ekam…Dve…Trini…and you continue,’ and that is what I’ve been doing ever since and life continues to move through the room. I saw life in Oz’s death — the way she lived with lightness and did beautiful, profound work. You don’t mess around with life and don’t wait for life to come to you. Choose to meet it now, in a way that is alive and vibrant and that’s what I want for everyone who walks through the door at Stillpoint. Possibility! Just focus on your breath with awareness and let go of concerns and be open to the experience of being alive. We have to feel as alive as we can. This experience made me understand life is fleeting and these little spaces of yoga — these still, small spaces are where we can experience life with awareness. Open up to the experience to be open to life. This experience gave me poetic licence to see and explore how yoga works on so many levels. It showed me how philosophy comes alive in us. You read about all this knowledge but this helped me experience that knowledge. In the death of Oz, in the death of someone who had so much to live for, I saw the work she would have done and that made me explore how I could make a difference and that is what teaching means to me. Oz's passing was tragic and profound and her death woke something up in me. I wouldn’t be the teacher that I am without that experience. Everything changes, nothing stays the same, we continue.”

Scott found life in death and in Bombay, Ankur battled hate with love. For as long as I've known Ankur, his lyrics spoke of love, freedom and romance but recently, his songs changed to more political themes and while they’re still songs about love, these new tracks reflected the current state of the world and especially India. “I stopped writing about love in the conventional sense because my music is inspired by life and everything that I feel. The current political scene has shaken our foundations — there is a lot of hatred, intolerance and imbalance and that affected me, so I used music and lyrics to write songs of protest against this hate culture. I will continue to write and create music to address these issues because I think it is important. Art can be political and create positive change. The last love song I wrote a few years ago was for my trolls on the Internet because only the force of love can remove hate. So, I was writing love songs for people who are busy hating (laughs). It’s not even about politics or religion. I just have a problem with inequality at any level and when I’m faced with it, I use music to find or create balance. Whenever any person or institution feels they are superior, that bothers me. Discrimination bothers me. I’m against discrimination whether it is people discriminating between men and women, or discriminating against gender fluid people or religion, caste, etc. I have a problem with anyone who feels superior and anyone who discriminates. I feel that the one force that unifies us is love and when we fall in love with something and someone, there is no space for discrimination. I’d like to think my music unifies people because it’s liberal — my anthem is Mohabbat Zindabad! Love will unite and love will win! I look forward to learning and expressing myself in new ways through art. But whatever I may be doing, you will always find me waving the flag of love,” asserts Ankur.

Art as Sādhanā

Scott’s creativity isn’t restricted to yoga either, he’s a gifted writer of poetry and uses it to express his feelings and as an abstract representation of yoga practice. “I love how words work and especially Haikus because they allow me to say so much within so little. Like the Yoga Sutras…I was always deeply moved by art and I wanted to use art to express yoga. Especially on Instagram, I didn’t want to post dramatic photos of postures and take that approach. I wanted to create something else that reflects the outcome of our practice and the philosophy. That happened with the Haikus. There is an outcome of practising and teaching and I like the idea of expressing that in an abstract way rather than just doing photos of asanas.”

In Ankur’s case, his music is his form of meditation and he likens it to yoga, “The disciplines of yoga, meditation and creating music are similar — the mind is completely absorbed and one-pointed. Any practice that dissolves the idea of time and space is meditative because it is rooted in the now. I’m only aware of the present when I’m creating music. For me, writing music means disconnecting from the clock — it even dissolves space for me because when I’m in my music, my surroundings fade away and I feel like a moment has been stretched into infinity — I love that feeling. That’s my sādhanā. But once I write a song and offer it to the world, that is the end of that journey for me. Once I offer it to the world, I don’t revisit a song or try to change it. Even if I feel it may be flawed — that is the way it is. I feel that even the flaws add to the beauty of it. My songs are like time stamps for where I was at that point in my life. I can listen to any of my songs and it’s like time travel — it takes me back to who I was at that time. Perfect or not doesn’t matter — life is not perfect (laughs). So I don’t revisit it or change my music. I make it and feel intensely what I have to feel in the moment and there is honesty and truth in that expression. When the song is done, it’s done. It is what it is,” says Ankur.

“As far as having a lucrative career in music goes, it is definitely less risky at present and there is scope to find a career in music both behind the scenes and as a full-time musician. You could be a musician, a support group, a manager, a booking agent, a lawyer who specialises in music copyrights, a recording engineer, a festival organiser, there are so many options. My advice to young musicians would be the same advice I follow for myself. Be honest with your artistry. Understand why you want to create music and why it’s important to you. Take time to introspect and ask yourself why you want to play, record or listen to music. This helps to navigate your career, set goals and streamline your thoughts. Staying honest also helps you to enjoy a good night’s sleep (laughs). And, respect art and artists. I find my inspiration in greats like Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, The Beatles, Jagjit Singh, Ghulam Ali Saab, Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan, Tom Waits, David Bowie. These are extraordinary people. But I’m also inspired by writers, photographers, painters… and anyone who can create and bring something new to the world. Originality inspires me.”

My dear readers, I started The Yoga Life to feature people and experiences that aren’t restricted to asanas or the conventional understanding of yoga. When I interview people like Ankur and Scott, it reminds me of how so many aspects of our lives and our choices shape who we become. People like my friends featured in this article use subtlety to create change, just like yoga. I’ve seen many teachers and students become enamoured and limited to their on-the-mat practice without exploring the mysticism of yoga and life, and I hope the articles in The Yoga life inspire and remind us all to tune into the mystery and romance of both life and death, and explore yoga beyond its physicality. This comes with deep concentration and a willingness to open our hearts and minds to life and everything that comes with it — the ugly and the beautiful.

Ankur’s latest release is a track called Aahista and it’s all about slowing down. I’ll leave you with this beautiful song and hope you enjoy listening to it as much as I did.

If you like what you read in The Yoga Life, check out my poetry on my Instagram handle, @sophiefrenchwrites

Photos courtesy: Ankur Tewari and Scott Johnson.